Template:Distinguish

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Template:Campaignbox French and Indian War | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

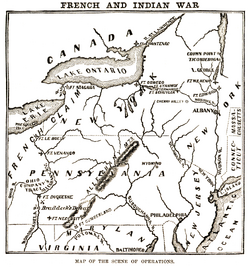

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was the North American chapter of the Seven Years' War, known in Canada (particularly in Quebec) as the War of the Conquest (French: Guerre de la Conquête). The name refers to the two main enemies of the British: the royal French forces and the various American Indian forces allied with them. The conflict, the fourth such colonial war between the nations of France and Great Britain, resulted in the British conquest of Canada. The outcome was one of the most significant developments in a century of Anglo-French conflict. To compensate its ally, Spain, for its loss of Florida, France ceded its control of French Louisiana west of the Mississippi. France's colonial presence north of the Caribbean was reduced to the tiny islands of Saint Pierre and Miquelon.

Naming the war

The conflict is known by several names. In British America, wars were often named after the sitting British monarch, such as King William's War or Queen Anne's War. Because there had already been a King George's War in the 1740s, British colonists named the second war in King George's reign after their opponents, and thus it became known as the French and Indian War.[1] This traditional name remains standard in the United States, although it obscures the fact that American Indians fought on both sides of the conflict.[2] American historians generally use the traditional name or the European title (the Seven Years' War). Other, less frequently used names for the war include the Fourth Intercolonial War and the Great War for the Empire.[1]

In Europe, the North American theatre of the Seven Years' War usually has no special name, and so the entire worldwide conflict is known as the Seven Years' War (or the Guerre de sept ans). The "Seven Years" refers to events in Europe, from the official declaration of war in 1756 to the signing of the peace treaty in 1763. These dates do not correspond with the actual fighting in North America, where the fighting between the two colonial powers was largely concluded in six years, from the Jumonville Glen skirmish in 1754 to the capture of Montreal in 1760.[1]

In Canada, both French- and English-speaking Canadians refer to it as the Seven Years' War[citation needed] (Guerre de Sept Ans). French Canadians may use the term "War of the Conquest" (Guerre de la Conquête), since it is the war in which New France was conquered by the British and became part of the British Empire, but that usage is never employed by English Canadians. This war is also one of America's "Forgotten Wars".

Impetus for war

Territorial expansion

There were numerous causes for the French and Indian War, which began less than a decade after France and Britain had fought on opposing sides in the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748). Both New France and New England wanted to expand their territories with respect to fur trading and other pursuits that matched their economic interests. Using trading posts and forts, both the British and the French claimed the vast territory between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River, from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico, known as the Ohio Country. English claims resulted from royal grants which had no definite western boundaries. The French claims resulted from La Salle's claim of the Mississippi River basin for France—its drainage area includes the Ohio River Valley. In order to secure these claims, both European powers took advantage of Native American factions to protect their territories and to keep the other from growing too strong.

Newfoundland's Grand Banks were fertile fishing grounds and coveted by both sides. Following the war, France ceded almost all of its claims to Britain, keeping only the islands of Saint Pierre and Miquelon, which allows them access to the Grand Banks to this day.

Religious ideology

The English colonists also feared papal influence in North America, as New France was administered by French governors and Roman Catholic hierarchy, and missionaries such as Armand de La Richardie were active during this period. For the predominantly Protestant British settlers, French control over North America could have represented a threat to their religious and other freedoms provided by English law.Template:Clarifyme Likewise, the French feared the anti-Catholicism prevalent among English colonists. In this period, Catholicism was still enduring persecution under English law.

Céloron's expedition

Map showing the 1750 possessions of Britain (pink), France (blue), and Spain (orange) in contemporary Canada and the United States.

In June 1747, Roland-Michel Barrin de La Galissonière, the Governor-General of New France, ordered Pierre-Joseph Céloron to lead an expedition to the Ohio Country with the objective of removing British influence from the area. Céloron was also to confirm the allegiance of the Native Americans inhabiting the territory to the French crown.

Céloron's expedition consisted of 213 soldiers of the Troupes de la marine (French Marines), who were transported by 23 canoes. The expedition left Lachine on June 15, 1749, and two days later reached Fort Frontenac. The expedition then continued along the shoreline of present-day Lake Erie. At the Chautauqua Portage (now Barcelona, New York), the expedition moved inland to the Allegheny River.

The expedition headed south to the Ohio River to present-day Pittsburgh, where Céloron buried lead plates engraved with the French claim to the Ohio Country. Whenever British merchants or fur-traders were encountered by the French, they were informed of the illegality of being on French territory and told to leave the Ohio Country.

When Céloron's expedition arrived at Logstown, the Native Americans in the area informed Céloron that they owned the Ohio Country and that they would trade with the British regardless of what the French told them to do.[3]

The French continued their expedition. At its farthest point south, Céloron's expedition reached the confluence of the Ohio River and the Miami River, which lay just south of the village of Pickawillany, the home of the Miami chief "Old Britain" (as styled by Céloron). Céloron informed "Old Britain" of the "dire consequences" of the elderly chief continuing to trade with the British. "Old Britain" ignored the warning. After his meeting, Céloron and his expedition began the trip home. They did not return to Montreal until November 10, 1749.

In his report, which extensively detailed the journey, Céloron wrote, "All I can say is that the Natives of these localities are very badly disposed towards the French, and are entirely devoted to the English. I don't know in what way they could be brought back."[3]

Langlade's expedition

On March 17, 1752, the Governor-General of New France, Marquis de la Jonquière died, and was temporarily replaced by Charles le Moyne de Longueuil. It was not until July 1, 1752 that his permanent replacement, Ange Duquesne de Menneville, arrived in New France to take over the post.

In the spring of 1752, Longueuil dispatched an expedition to the Ohio River area. The expedition was led by Charles Michel de Langlade, an officer in the Troupes de la Marine. Langlade was given 300 men comprising members of the Ottawa and French-Canadians. His objective was to punish the Miami people of Pickawillany for not following Céloron's orders to cease trading with the British.

At dawn on June 21, 1752, the French war party attacked the British trading centre at Pickawillany, killing fourteen people of the Miami nation, including Old Britain. The expedition then returned home.

Marin's expedition

In the spring of 1753, Paul Marin de la Malgue was given command of a 2,000 man force of Troupes de la Marine and Indians. His orders were to protect the King's land in the Ohio Valley from the British. Marin followed the route that Céloron had mapped out four years earlier, but where Céloron had limited the record of French claims to the burial of lead plates, Marin constructed and garrisoned forts. The first fort constructed by Paul Marin was Fort Presque Isle (now Erie, Pennsylvania) on Lake Erie's south shore. He then had a road built to the headwaters of LeBoeuf Creek. Marin then constructed a second fort at Fort Le Boeuf (Waterford, Pennsylvania), designed to guard the headwaters of LeBoeuf Creek.

The earliest authenticated portrait of George Washington shows him wearing his colonel's uniform of the Virginia Regiment from the French and Indian War. This portrait was painted years after the war, in 1772.

Tanaghrisson's proclamation

On September 3, 1753, Tanaghrisson, Chief of the Mingo, arrived at Fort Le Boeuf. He hated the French because, as legend had it, the French had killed and eaten his father. Tanaghrisson told Marin, "I shall strike at whoever...",[4] threatening the French.

The show of force by the French had alarmed the Iroquois in the area. They sent Mohawk runners to William Johnson's manor in Upper New York. Johnson, known to the Iroquois as "Warraghiggey", meaning "He who does big business", had become a respected member of the Iroquois Confederacy in the area. In 1746, Johnson was made a colonel of the Iroquois, and later a colonel of the Western New York Militia.

At Albany, New York, Governor Clinton of New York and Chief Hendrick met, along with other officials from a handful of American colonies. Chief Hendrick insisted that the British abide by their obligations and block French expansion. When an unsatisfactory response was offered by Clinton, Chief Hendrick proclaimed that the "Covenant Chain", a long-standing friendly relationship between the Iroquois Confederacy and the British Crown, was broken.

Dinwiddie's reaction

Governor Robert Dinwiddie of Virginia found himself in a predicament. Many merchants had invested heavily in fur trading in the Ohio Country. If the French made good on their claim to the Ohio Country and drove out the British, then the Virginian merchants would lose a lot of money.

To counter the French military presence in Ohio, in October 1753 Dinwiddie ordered Major George Washington of the Virginia militia to deliver a message to the commander of the French forces in the Ohio Country, Jacques Legardeur de Saint-Pierre. Washington, along with his interpreter Jacob Van Braam and several other men, left for Fort Le Boeuf on October 31.

Washington's map of the Ohio River and surrounding region containing notes on French intentions, 1753 or 1754.

A few days later, Washington and his party arrived at Wills Creek (near modern Cumberland, Maryland). Here Washington enlisted the help of Christopher Gist, a surveyor who was familiar with the area. Washington and his party arrived at Logstown on November 24. At Logstown, Washington met with Tanaghrisson, and convinced him to accompany his small group to Fort Le Boeuf.

On December 12, Washington and his men reached Fort Le Boeuf. Saint-Pierre invited Washington to dine with him that evening. Over dinner, Washington presented Saint-Pierre with the letter from Dinwiddie that demanded an immediate French withdrawal from the Ohio Country. Saint-Pierre was quite civil in his response, saying, "As to the Summons you send me to retire, I do not think myself obliged to obey it."[5] The French explained to Washington that France's claim to the region was superior to that of the British, since René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle had explored the Ohio Country nearly a century earlier.[6]

Washington's party left Fort Le Boeuf early on December 16, arriving back in Williamsburg on January 16, 1754. In his report, Washington stated, "The French had swept south",[7] constructing and occupying forts at Presque Isle, Le Boeuf and Venango.

War

The French and Indian War was the last of four major colonial wars between the British, the French, and their Native American allies. Unlike the previous three wars, the French and Indian War began on North American soil and then spread to Europe in 1756, where Britain and France continued fighting the Seven Years' War. The war in North America was largely over in 1760, while the war in Europe continued until 1763.

Native Americans fought on both sides of the conflict, but were primarily allied to the French. The notable exception was the Iroquois Confederacy, which sided with the American colonies and Britain. The first major event of the war was in 1754, when a Virginia provincial major named George Washington, then twenty-one years of age, was sent to negotiate boundaries with the French, who were unwilling to give up their fortified positions. Washington led a group of Virginian colonial troops to confront the French at Fort Duquesne (the site of modern Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania). Washington stumbled upon the French about 40 miles before reaching Fort Duquesne. In the ensuing skirmish, a French Officer named Joseph Coulon de Jumonville was killed, news of which would have certainly provoked a strong French response. Washington pulled back several miles and established Fort Necessity. The French attacked this position on July 3, forcing Washington to negotiate a withdrawal under arms.

In 1755, the British sent General Edward Braddock with about 2,000 army troops and provincial militia on an expedition to take Fort Duquesne. The expedition ended in disaster, with Braddock mortally wounded. Two future opponents in the American Revolutionary War, Washington and Thomas Gage, played key roles in organizing the retreat. The failure of Braddock's expedition was offset by British victories at Lake George, which secured the Hudson River valley, and at Fort Beauséjour, where the capture of that French fort secured the frontier of Nova Scotia. An unfortunate consequence of the latter was the subsequent forced deportation of the Acadian population of Nova Scotia and the Beaubassin region of Acadia, which effectively came under British control.

However, 1756 and 1757 were filled with French military victories, in which they consolidated control over Lake Ontario, Lake Champlain and the upper Mohawk River valley, with victories at Fort Bull, Fort Oswego, and Fort William Henry. This string of bad news led to a change of political control over the war in Britain. William Pitt became the Secretary of State responsible for the colonies, and he proceeded to implement plans largely developed by his predecessor, Lord Loudoun, to once and for all drive the French from North America.

The Victory of Montcalm's Troops at Carillon by Henry Alexander Ogden.

Pitt's plan called for three major offensive actions involving large numbers of regular troops, supported by provincial militias, aimed at capturing the heartlands of New France. In 1758 two of these expeditions were successful, with Fort Duquesne and Louisbourg falling to sizable British forces. The third was stopped with the improbable French victory in the Battle of Carillon, in which 4,000 Frenchmen famously defeated a British force of 16,000 outside the fort the French called Carillon and the British called Ticonderoga.

British victories continued in the same theaters in 1759, when they finally captured Ticonderoga, James Wolfe defeated Montcalm at Quebec, and victory at Fort Niagara successfully cut off the French frontier forts further to the west and south. The victory was made complete in 1760, when, despite losing outside Quebec City in the Battle of Sainte-Foy, the British were able to prevent French relief of their colonies in the naval Battle of the Restigouche while their armies marched on Montreal from the south and the west.

In September of 1760, Pierre François de Rigaud, Marquis de Vaudreuil-Cavagnal, the King's Governor of New France, negotiated a surrender with British General Jeffrey Amherst. General Amherst granted Vaudreuil's request that any French residents who chose to remain in the colony would be given freedom to continue worshiping in their Roman Catholic tradition, continued ownership of their property, and the right to remain undisturbed in their homes. The British provided medical treatment for the sick and wounded French soldiers and French regular troops were returned to France aboard British ships with an agreement that they were not to serve again in the present war.

Outcome

The descent of the French on St. John's, Newfoundland, 1762

Most of the North American fighting ended with the surrender of Montreal; notable late battles included the British capture of Spanish Havana and a French attempt to gain control of Newfoundland in the Battle of Signal Hill, both in 1762. The war officially ended with the signing of the Treaty of Paris on February 10, 1763. The British offered France a choice of its North American possessions east of the Mississippi except Saint Pierre and Miquelon or the two small islands off Newfoundland and the Caribbean islands of Guadeloupe and Martinique, which had been occupied by the British. France chose to cede Canada. The economic value of the Caribbean islands to France was greater than that of Canada because of their rich sugar crops, and the fact that they were easier to defend. The British, however, were happy to take New France, as defence was not an issue, and they already had many sources of sugar. Spain gained Louisiana, including New Orleans, in compensation for its loss of Florida to the British.

Map showing British territorial gains following the Treaty of Paris in pink, and Spanish territorial gains after the Treaty of Fontainebleau in yellow.

Britain gained control of French Canada, a colony containing approximately 65,000 primarily French-speaking Roman Catholic residents. Early in the war, in 1755, the British had begun expelling French settlers from Acadia (some of whom eventually settled Louisiana, creating the Cajun population). Now at peace, and eager to secure control of its hard-won colony, Great Britain found itself obliged to make concessions to its newly conquered subjects; this was achieved with the Quebec Act of 1774. The history of the Seven Years' War, particularly the siege of Quebec and the death of British Brigadier General James Wolfe, generated a vast number of ballads, broadsides, images, maps and other printed materials, which testify to how this event continued to capture the imagination of the British public long after Wolfe's death in 1759.[8]

The European theatre of the war was settled by the Treaty of Hubertusburg on February 15, 1763. The war changed economic, political, and social relations between Britain and its colonies. It plunged Britain into debt, which the Crown chose to pay off by increasing tax revenues from its colonies. The British were also keen on keeping the peace in North America, especially on the colonies' western frontiers, so in an effort to appease the various Indian tribes the Royal Proclamation of 1763 included provisions prohibiting colonists from engaging in further expansion west of the Appalachian Mountains. In taking these measures the British government failed to appreciate that by eliminating the French threat in North America the British had in fact removed one of the strongest incentives the colonies had for retaining their links with Great Britain. Unpopular taxes, restrictions on colonial expansion and concessions given to Quebec's Catholic population all contributed to the beginning the American Revolutionary War.

Timeline

| Year | Dates | Event | Location | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1754 | May 28 July 3 |

Battle of Jumonville Glen Battle of the Great Meadows (Fort Necessity) |

Uniontown, Pennsylvania Uniontown, Pennsylvania |

British victory French victory |

| 1755 | May 29 – July 9 June 3 – 16 July 9 September 8 |

Braddock expedition Battle of Fort Beauséjour Battle of the Monongahela Battle of Lake George |

Western Pennsylvania Sackville, New Brunswick Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania Lake George, New York |

French victory British victory French victory British victory |

| 1756 | March 27 August 10 – 14 September 8 |

Battle of Fort Bull Battle of Fort Oswego Kittanning Expedition |

Rome, New York Oswego, New York Kittanning, Pennsylvania |

French victory French victory British victory |

| 1757 | August 2 – 9 December 8 |

Battle of Fort William Henry Second Battle of Bloody Creek |

Lake George, New York Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia |

French victory French victory |

| 1758 | June 8 – July 26 July 7 – 8 August 25 September 14 October 12 |

Siege of Louisbourg Battle of Carillon (Fort Ticonderoga) Battle of Fort Frontenac Battle of Fort Duquesne Battle of Fort Ligonier |

Louisbourg, Nova Scotia Ticonderoga, New York Kingston, Ontario Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania Western Pennsylvania |

British victory British victory British victory French victory British victory |

| 1759 | July 26 – 27 July 6 – 26 July 31 September 13 |

Battle of Ticonderoga (1759) Battle of Fort Niagara Battle of Beauport Battle of the Plains of Abraham |

Ticonderoga, New York Fort Niagara, New York Quebec City Quebec City |

British victory British victory French victory British victory |

| 1760 | April 28 July 3 – 8 August 16 – 24 |

Battle of Sainte-Foy Battle of Restigouche Battle of the Thousand Islands |

Quebec City Pointe-à-la-Croix, Quebec Ogdensburg, New York |

French victory British victory British victory |

| 1762 | September 15 | Battle of Signal Hill | St. John's, Newfoundland | British victory |

| 1763 | February 10 | Treaty of Paris | Paris, France |

Battles and expeditions

- United States

- Battle of Jumonville Glen (May 28, 1754)

- Battle of Fort Necessity, aka the Battle of Great Meadows (July 3, 1754)

- Braddock Expedition (Battle of the Monongahela aka Battle of the Wilderness) (July 9, 1755)

- Kittanning Expedition (climax September 8, 1756)

- Battle of Fort Duquesne (September 14, 1758)

- Battle of Fort Ligonier (October 12, 1758)

- Forbes Expedition (climax November 25, 1758)

- Province of New York

- Battle of Lake George (1755)

- Battle of Fort Oswego (August, 1756)

- Battle on Snowshoes (January 21, 1757)

- Battle of Fort Bull (March 27, 1756)

- Battle of Sabbath Day Point (July 26, 1757)

- Battle of Fort William Henry (August 9, 1757)

- Attack on German Flatts (1757) (November 12, 1757)

- Battle of Carillon (July 8, 1758)

- Battle of Ticonderoga (1759)

- Battle of La Belle-Famille (July 24, 1759)

- Battle of Fort Niagara (1759)

- Battle of the Thousand Islands, 16-August 25, 1760

- West Virginia

- Battle of Great Cacapon (April 18, 1756)

- Canada

- New Brunswick

- Battle of Fort Beauséjour (June 16, 1755)

- Nova Scotia

- Siege of Louisbourg (June 8 - July 26, 1758)

- Ontario

- Battle of Fort Frontenac (August 25, 1758)

- Battle of the Thousand Islands, 16-August 25, 1760

- Quebec

- Battle of Beauport (July 31, 1759)

- Battle of the Plains of Abraham (September 13, 1759)

- Battle of Sainte-Foy (April 28, 1760)

- Battle of Restigouche, July 3-8, (1760)

- Newfoundland

- Battle of Signal Hill September 15, 1762

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Anderson, Crucible of War, 747.

- ↑ Jennings, Empire of Fortune, xv.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Fowler, Empires at War, 14.

- ↑ Fowler, Empires at War, 31.

- ↑ Fowler, Empires at War, 35.

- ↑ Ellis, His Excellency George Washington, 5.

- ↑ Fowler, Empires at War, 36.

- ↑ Virtual Vault, an online exhibition of Canadian historical art at Library and Archives Canada

References

- Anderson, Fred (2000). Crucible of War: The Seven Years' War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754-1766. New York: Knopf. ISBN 0375406425.

- Anderson, Fred (2005). The War that Made America: A Short History of the French and Indian War. New York: Viking. ISBN 0670034541. Released in conjunction with the 2006 PBS miniseries The War that Made America.

- Ellis, Joseph J. (2004). His Excellency George Washington. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 1400032539.

- Fowler, W. M. (2005). Empires at War: The French and Indian War and the Struggle for North America, 1754-1763. New York: Walker. ISBN 0802714110.

- Jennings, Francis (1988). Empire of Fortune: Crowns, Colonies, and Tribes in the Seven Years War in America. New York: Norton. ISBN 0393306402.

- Virtual Vault, an online exhibition of Canadian historical art at Library and Archives Canada

Further reading

- Eckert, Allan W. Wilderness Empire. Bantam Books, 1994, originally published 1969. ISBN 0-553-26488-5. Second volume in a series of historical narratives, with emphasis on Sir William Johnson. Academic historians often regard Eckert's books, which are written in the style of novels, to be fiction.

- Parkman, Francis. Montcalm and Wolfe: The French and Indian War. Originally published 1884. New York: Da Capo, 1984. ISBN 0-306-81077-8.

See also

- Fort at Number 4

- French and Indian Wars (article includes King William's War, Queen Anne's War, King George's War, and the French and Indian War.)

- Great Upheaval

- Military history

- New Hampshire Provincial Regiment

- Join, or Die, the famous cartoon by Benjamin Franklin

- Pontiac's Rebellion

- Rogers' Rangers

- Mitchell Map

- List of conflicts in Canada

- List of conflicts in the United States

- List of historical novels, under United States - Colonial

External links

Template:Commons cat

- The French and Indian War Website

- Historical Preservation Archive: Transcribed Articles & Documents

- The War That Made America from PBS

cs:Francouzsko-indiánská válka da:Franske og indianske krig de:Franzosen- und Indianerkrieg es:Guerra Franco-india eu:Gerra frantses-indiarra fr:Guerre de la Conquête id:Perang Perancis dan Indian ia:Guerra franco-indigena it:Guerra franco-indiana he:מלחמת הצרפתים והאינדיאנים ka:ფრანგებისა და ინდიელების ომი 1754-1763 nl:Franse en Indiaanse Oorlog ja:フレンチ・インディアン戦争 no:Den franske og indianske krig pl:Brytyjska wojna z Indianami i Francuzami pt:Guerra Franco-Indígena ru:Франко-индейская война simple:French and Indian War sl:Francoska in indijanska vojna zh:法國-印第安戰爭