| Battle of Cowpens | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of American Revolutionary War | |||||||

Painted by William Ranney in 1845, this depiction of the Battle of Cowpens shows an unnamed black soldier (left) firing his pistol and saving the life of Colonel William Washington (on white horse in center). | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders | |||||||

| Brig. Gen Daniel Morgan | Lt. Col Banastre Tarleton | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1,000[2] | 1,100[3] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 25 killed 124 wounded [4] |

110 killed 229 wounded 900 captured 2 guns lost [5][6] | ||||||

The Battle of Cowpens (January 17, 1781) was a decisive victory by American Revolutionary forces under Brigadier General Daniel Morgan, in the Southern campaign of the American Revolutionary War. It was a turning point in the reconquest of South Carolina from the British.

The Colonial force[]

The Colonial forces were commanded by Brigadier-General Daniel Morgan. Although Morgan claimed in his official report to have had only a few over 800 men at Cowpens, historian Lawrence Babits, in his detailed study of the Battle, estimates the real numbers as:

- A battalion of Continental infantry under Lt-Col John Eager Howard, with one company from Delaware, one from Virginia and three from Maryland; each with a strength of sixty men (300)[7]

- A company of Virginia State troops under Captain John Lawson[8] (75)[9]

- A company of South Carolina State troops under Captain Joseph Pickens (60)[10]

- A small company of North Carolina State troops under Captain Henry Connelly (number not given)[8]

- A Virginia Militia battalion under Frank Triplett[11] (160)[12]

- Two companies of Virginia Militia under Major David Campbell (50)[13]

- A battalion of North Carolina Militia under Colonel Joseph McDowell (260–285)[14]

- A brigade of four battalions of South Carolina Militia under Colonel Andrew Pickens, comprising a three-company battalion of the Spartanburg Regiment under Lt-Col Benjamin Roebuck; a four-company battalion of the Spartanburg Regiment under Col John Thomas; five companies of the Little River Regiment under Lt-Col Joseph Hayes and seven companies of the Fair Forest Regiment under Col Thomas Brandon. Babits states[15] that these battalion “ranged in size from 120 to more than 250 men”. If Roebuck’s three companies numbered 120 and Brandon’s seven companies numbered 250, then Thomas’s four companies probably numbered about 160 and Hayes’s five companies about 200, for a total of (730)

- Three small companies of Georgia Militia commander by Major Cunningham[16] who numbered (55)[17]

- Detachments of the 1st and 3rd Continental Light Dragoon (both recruited mainly in Virginia) under Lt-Col William Washington (82)[18]

- Detachments of State Dragoons from North Carolina and Virginia (30)[19]

- A detachment of South Carolina State Dragoons, with a few mounted Georgians, commanded by Major James McCall (25)[20]

- A company of newly-raised volunteers from the local South Carolina Militia commanded by Major Benjamin Jolly (45)[21]

The figures given by Laurence E. Babits total 82 Continental Light Dragoons; 55 State Dragoons; 45 Militia Dragoons; 300 Continental infantry; about 150 State infantry and 1,255-1,280 Militia infantry, for a total of 1,887–1,912 officers and men.

Broken down by state, there were about 855 South Carolinians; 442 Virginians; 290–315 North Carolinians; 180 Marylanders; 60 Georgians and 60 Delawareans.

Morgan's Continentals were veterans, and many of his militia, which included some Overmountain Men, had seen service at the Battle of Musgrove Mill and the Battle of Kings Mountain.

The British force[]

"Lieutenant-Colonel Banastre Tarleton" by Sir Joshua Reynolds.

The British were commanded by Colonel Banastre Tarleton. The British force comprised:

- Loyalist Legion: 250 cavalry and 200 infantry,[22]

- A troop of the 17th Light Dragoons (50),

- A battery of the Royal Artillery (24) with two 3-pounder cannons[23]

- The 7th (Royal Fusiliers) Regiment (177)

- The light infantry company of the 16th Regiment (42)

- The 71st (Fraser's Highlanders) Regiment under Major Arthur MacArthur (334)

- The light company of the Loyalist Prince of Wales' American Regiment (31)

- A company of Loyalist guides (50)

A total of over 1,150 officers and men.[24]

Broken down by troop classification, there were 300 cavalry, 553 regulars, 24 artillerymen and 281 militia. Tarleton’s men from the Royal Artillery, 17th Light Dragoons, 16th Regiment and 71st Regiment were reliable and good soldiers: but the detachment of the 7th Regiment were raw recruits who had been intended to reinforce the garrison of Fort Ninety-Six where they could receive further training rather than go straight into action.[25] Tarleton's own unit, the British Legion were formidable "in a pursuit situation"[26] but had an uncertain reputation “when faced with determined opposition”.[26]

The situation[]

General Cornwallis instructed Tarleton and his Legion, who had been successful at battles such as Camden and Waxhaw in the past, to destroy Morgan's command. Tarleton's previous victories had been won by bold attacks, often despite being outnumbered. American commander Nathanael Greene had taken the daring step of dividing his army, detaching Morgan away from the main Patriot force. Morgan called Americans to gather at the cow pens (a grazing area), which were a familiar landmark. Tarleton attacked with his customary boldness but without regard for the fact Morgan had much more time to prepare. Tarleton was consequently caught in a textbook double envelopment. Tarleton's forces were virtually destroyed, but he managed to flee the battlefield with perhaps 250 men.

Reenactors at Cowpens Battlefield

Battle of Cowpens Reenactment, 225th anniversary, January 14, 2006.

Daniel Morgan knew that he should use the unique landscape of Cowpens and the time available before Tarleton's arrival to his advantage. Furthermore, he knew his men and his opponent, knew how they would react in certain situations, and used this knowledge to his advantage.[27] To begin with, the location of his forces were contrary to any existing military doctrine: he placed his army between the Broad and Pacolet River, thus making escape impossible if the army was routed. His reason for cutting off escape was obvious: to ensure that the untrained militiamen would not, as they had been accustomed to do, turn in flight at the first hint of battle and abandon the regulars. (The Battle of Camden had ended in disaster when the militia, which was half of the American force, broke and ran as soon as the shooting started.) Selecting a hill as the center of his position, he placed his Continental infantry on it, deliberately leaving his flanks exposed to his opponent. Morgan reasoned that Tarleton would attack him head on, and he made his tactical preparations accordingly. He set up three lines of soldiers: one of skirmishers (sharpshooters); one of militia; and a main one. The 150 select skirmishers were from North Carolina (Major McDowell) and Georgia (Major Cunningham). Behind these men were 300 militiamen under the command of Andrew Pickens.

Realizing that poorly-trained militia were unreliable in battle, especially when they were under attack from cavalry, Morgan decided to ask the militia to fire two shots and then retreat, so he could have them re-form under cover of the reserve (cavalry commanded by William Washington and James McCall) behind the third, more experienced line of militia and continentals. The movement of the militia in the second line would mask the third line to the British. The third line, composed of the remainder of the forces (about 550 men) was composed of Continentals from Delaware and Maryland, and militiamen from Georgia and Virginia. Colonel John Eager Howard commanded the Continentals and Colonels Tate and Triplett the militia. The goal of this strategy was to weaken and disorganize Tarleton's forces (which would be attacking the third line uphill) before attacking and defeating them. Howard’s men would not be unnerved by the militia’s expected move, and unlike the militia they would be able to stand and hold, especially since the first and second lines, Morgan felt, would have inflicted both physical and psychological damage on the advancing British before the third line came into action.

Additionally, by placing his men downhill from the advancing British lines, Morgan exploited the British tendency to fire too high in battle. The downhill position of his forces allowed the British forces to be silhouetted against the morning sunlight, providing easy targets for Patriot troops. With a ravine on their right flank and a creek on their left flank, Morgan's forces were protected against British flanking maneuvers at the beginning of the battle. Morgan insisted,[28]

"the whole idea is to lead Benny [Tarleton] into a trap so we can beat his cavalry and infantry as they come up those slopes. When they've been cut down to size by our fire, we'll attack them."

In developing his tactics at Cowpens, as historian John Buchanan wrote, Morgan may have been "the only general in the American Revolution, on either side, to produce a significant original tactical thought.”

Tarleton's approach[]

Battle of Cowpens Reenactment, 225th anniversary, January 14, 2006

At 2:00 a.m. on January 17, 1781, Tarleton roused his troops and continued his march to the Cowpens. Lawrence Babits states that, "in the five days before Cowpens, the British were subjected to stress that could only be alleviated by rest and proper diet". He points out that “in the forty-eight hours before the battle, the British ran out of food and had less than four hours’ sleep”.[29] Over the whole period, Tarleton’s brigade did a great deal of rapid marching across difficult terrain. Babits concludes that they reached the battlefield exhausted and malnourished. Tarleton sensed victory and nothing would persuade him to delay. His Tory scouts had told him of the countryside Morgan was fighting on, and he was certain of success because Morgan's soldiers, mostly militiamen, seemed to be caught between mostly experienced British troops and a flooding river. As soon as he reached the spot, he formed a battle line, which consisted of dragoons on his flanks, with his two grasshopper cannon in between the British Regulars and American Loyalists. More cavalry and the 71st Highlanders composed his reserve. Tarleton’s plan was simple and direct. Most of his infantry (including that of the Legion) would be assembled in linear formation and move directly upon Morgan. The right and left flanks of this line would be protected by dragoon units. In reserve he would hold his 250-man battalion of Scottish Highlanders (71st Regiment of Foot), commanded by Major Arthur MacArthur, a professional soldier of long experience who had served in the Dutch Scotch Brigade. Finally, Tarleton kept the 200-man cavalry contingent of his Legion ready to be unleashed when the Americans broke and ran.

The Battle[]

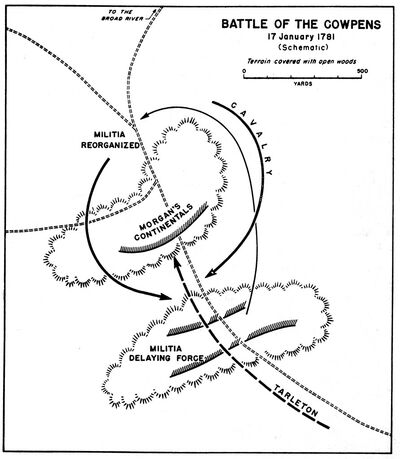

Battle of Cowpens 17 January 1781. Right flank(cavalry) of Lt. Col.William Washington and (left flank) the militia returned to enfilade

Morgan's strategy worked perfectly. The British drove in successive lines, anticipating victory only to encounter another, stronger line after exerting themselves and suffering casualties. The depth of the American lines gradually soaked up the shock of the British advance.

After killing or wounding fifteen dragoons, the skirmishers retreated. The British pulled back temporarily but attacked again, this time reaching the militiamen, who (as ordered) poured two volleys into the British who—with 40% of their casualties being officers—were astonished and confused. They reformed and continued to advance. Tarleton responded by ordering one of his officers, Ogilvie, to charge with some dragoons into the "defeated" Americans. His men moved forward in regular formation and were momentarily checked by the militia musket fire but continued to advance. Pickens' militia broke and apparently fled to the rear and were eventually reorganized.

Taking the withdrawal of the first two lines as a full blown retreat, the British advanced headlong into the awaiting final line of disciplined regulars which firmly held on the hill.

Despite this, Tarleton believed he could still win with only one line of Americans left and sent his infantry in for a frontal attack. The Highlanders were ordered to flank the Americans. Under the direction of Howard, the Americans retreated. Flushed with victory and now disorganized, the British ran after them. Abruptly, Howard pulled an about-face, fired an extremely devastating volley into his enemy, and then charged. Triplett's riflemen attacked and the cavalry of Washington and McCall charged. Completely routed, the dragoons fled to their own rear. Having dismantled Ogilvie's forces, Washington charged into the British right flank and rear, while the militia, having re-formed, charged out from behind the hill—completing a 360-degree circle around the American position—to hit the British left.

The flag flown during the battle became known as the Cowpens flag

The shock of the sudden charge, coupled with the reappearance of the American militiamen on the flanks where Tarleton's exhausted men expected to see their own cavalry, proved too much for the British. Nearly half of the British and Loyalist infantrymen fell to the ground whether they were wounded or not. Their ability to fight had gone. Historian Lawrence Babits diagnoses "combat shock" as the cause for this abrupt British collapse—the effects of exhaustion, hunger and demoralization suddenly catching up with them.[30] Caught in a clever double envelopment that has been compared with the Battle of Cannae[1], many of the British surrendered. With Tarleton's right flank and center line collapsed, there remained only a minority of the 71st Highlanders who were still putting up a fight against part of Howard's line. Tarleton, realizing the desperate seriousness of what was occurring, rode back to his one remaining unit that was in one piece, the Legion Cavalry. Desperate to save something, Tarleton assembled a group of cavalry and tried to save the two cannon he had brought with him, but they had been taken. Tarleton with a few remaining horsemen rode back into the fight, but after clashing with Washington’s men, he too retreated from the field. He was stopped by Colonel Washington, who attacked him with his saber, calling out, "Where is now the boasting Tarleton?". A Cornet of the 17th, Thomas Patterson, rode up to strike Washington but was shot by Washington's orderly trumpeter. Tarleton then shot Washington's horse from under him and fled. Only the Royal Artillery gunners fought till they were all killed or wounded.

Morgan's troops took 652 British and Loyalist troops—a devastating blow. Even worse for the British, the forces lost, especially Tarleton's Legion and the dragoons, constituted the cream of Cornwallis' army. The number of British killed was claimed by the victorious Americans variously as 100, 110 and 120. Whatever the number killed in action, what counted was that Tarleton's brigade had been all but wiped out as a fighting force.

Historian Lawrence Babits has demonstrated that Morgan's official report of 73 casualties appears to have only included his Continental troops. From surviving records, he has been able to identify by name 128 Patriot soldiers who were either killed or wounded at Cowpens. He also presents an entry in the North Carolina State Records that shows 68 Continental and 80 Militia casualties. It would appear that both the number of Morgan's casualties and the total strength of his force were about double what he officially reported.[31]

It was claimed by some of the Patriots after the battle that Tarleton had ordered his men, before they went into action, to take no prisoners. This may have been "black propaganda" of the sort that flourished amid the brutal conflict in the Carolinas during the Revolution. Tarleton's British Legion Cavalry were notorious for the way that they ruthlessly pursued defeated opponents, cutting them down as they tried to surrender. As a result, Tarleton was given the nickname "Barbarous Ban" by the Patriot press, a title that Tarleton relished since he felt it gave his command an advantage. But it is notable that nearly every time they defeated the enemy — Monck's Corner, Lenud's Ferry, Camden, Catawba Ford — Tarleton's men did in fact take some prisoners. Even at the Battle of Waxhaw Creek (alias The Buford Massacre), where Tarleton's men killed a high proportion of their opponents, they granted quarter to 203 Patriots.[32] By Tarleton's own account, his horse was shot from under him in the charge at Waxhaw Creek and chaos erupted when his men believed he had been killed. In the end, 113 Americans were killed and another 203 captured, 150 of whom were so badly wounded that they had to be left behind. Tarleton's casualties were five killed and 12 wounded.[32] This does not disprove the allegation that Tarleton had issued a "no quarter" order before Cowpens but no explanation has been offered as to why Tarleton would suddenly have adopted this policy.

Tarleton's apparent recklessness in pushing his command so hard in pursuit of Morgan that they reached the battlefield in desperate need of rest and food may be explained by the fact that, up until Cowpens, every battle that he and his British Legion had fought in the South had been a relatively easy victory. He appears to have been so concerned with pursuing Morgan that he quite forgot that it was necessary for his men to be in a fit condition to fight a battle once they caught him.

Nevertheless, Daniel Morgan, known affectionately as "The Old Waggoner" to his men, had fought a masterly battle. His tactical decisions and personal leadership had allowed a force consisting mainly of militia to fight according to their strengths to win one of the most complete victories of the war.

Aftermath[]

Battlefield monument

Coming in the wake of the American debacle at Camden, Cowpens was a surprising victory and a turning point that changed the psychology of the entire war—"spiriting up the people", not only those of the backcountry Carolinas, but those in all the Southern colonies. As it was, the Americans were encouraged to fight further, and the Loyalists and British were demoralized. Furthermore, its strategic result—the destruction of an important part of the British army in the South—was incalculable toward ending the war. Along with the British defeat at the Battle of Kings Mountain, Cowpens was a decisive blow to Cornwallis, who might have defeated much of the remaining resistance in South Carolina had Tarleton won at Cowpens. Instead, the battle set in motion a series of events leading to the end of the war. Cornwallis abandoned his pacification efforts in South Carolina, stripped his army of its excess baggage, and pursued Greene's force into North Carolina. After a long chase Cornwallis met Greene at Guilford Court House, winning a pyrrhic victory that so damaged his army that he withdrew to Yorktown, Virginia, to rest and refit. This gave Washington the opportunity, which he seized, to trap and defeat Cornwallis at the Battle of Yorktown, which caused the British to give up their efforts to regain their colonies.

In the opinion of John Marshall,[33] "Seldom has a battle, in which greater numbers were not engaged, been so important in its consequences as that of Cowpens." It gave General Nathanael Greene his chance to conduct a campaign of "dazzling shiftiness" that led Cornwallis by "an unbroken chain of consequences to the catastrophe at Yorktown which finally separated America from the British crown."[34]

Memorials[]

- The battle site is preserved at Cowpens National Battlefield.

- Two ships of the U.S. Navy have been named USS Cowpens in honor of the battle.

Notes[]

- ↑ Family - Doty - Battle of Cowpens

- ↑ Simms, Oliphant p.175

- ↑ Alden p.462

- ↑ The South Carolina Encyclopedia pg 235 by Walter B. Edgar

- ↑ Babits, Lawrence E. (1998). A Devil of a Whipping: The Battle of Cowpens Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-2434-8, page 142.

- ↑ History of South Carolina, by Yates Snowden, Harry Gardner Cutler, page 406.

- ↑ Babits, pages 27–29.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Babits, page 28.

- ↑ Babits, page 77.

- ↑ Babits, page 73.

- ↑ Babits, page 33.

- ↑ Babits, page 104.

- ↑ Babits, page 34.

- ↑ Babits, pages 35–36.

- ↑ Babits, page 36.

- ↑ Babits, page 40.

- ↑ Babits, page 187, Note 14.

- ↑ Babits, page 40–41.

- ↑ Babits, page 175, Note 101.

- ↑ Babits, pages 41–42 and page 175, Note 101.

- ↑ Babits, pages 41–42.

- ↑ Babits, page 46, “British Legion Infantry strength at Cowpens was between 200 and 271 enlisted men”. However, this statement is referenced to a note on pages 175–176, which says, “The British Legion infantry at Cowpens is usually considered to have had about 200–250 men, but returns for the 25 December 1780 muster show only 175. Totals obtained by Cornwallis, dated 15 January, show that the whole legion had 451 men, but approximately 250 were dragoons”. There would therefore appear to be no evidence for putting the total strength of the five British Legion Light Infantry companies at more than 200.

- ↑ Bearss, Edwin C., Battle of Cowpens, Originally published by Office of Archeology and Historic Preservation, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, October 15, 1967, ISBN 1-57072-045-2. Reprinted 1996 by The Overmountain Press. Found at http://www.nps.gov/archive/cowp/bearss/chap1.htm .

- ↑ All unit strengths from Babits.

- ↑ 70th Congress, 1st Session House Document No. 328: Historical Statements Concerning the Battle of King’s Mountain and the Battle of the Cowpens pp. page 53. United States Government Printing Office (1928). Retrieved on 2007-12-10.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Babits, page 46.

- ↑ Fowler, under External links.

- ↑ Brooks, Victor; Robert Hohwald (1999). How America Fought Its Wars: Military Strategy from the American Revolution to the Civil War. Da Capo Press. p. 134. ISBN 1580970028.

- ↑ Babits, page 156.

- ↑ Babits discusses this phenomenon fully on pages 155–159

- ↑ Babits, pages 150–152.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Boatner, page 1174.

- ↑ Marshall, Volume I, page 404.

- ↑ Trevelyan, Volume II, page 141.

Bibliography[]

- Alden, John R. (1989). A History of the American Revolution.

- Babits, Lawrence E. (1998). A Devil of a Whipping: The Battle of Cowpens. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-2434-8.

- Bearss, Edwin C. (1996). The Battle of Cowpens: A Documented Narrative and Troop Movement Maps. Johnson City, Tennessee: Overmountain Press. ISBN 1570720452.

- Boatner, Mark Mayo (1966). Cassell's Biographical Dictionary of the American War of Independence, 1763–1783. London: Cassell. ISBN 0304292966.

- Buchanan, John (1997). The Road to Guilford Courthouse: The American Revolution in the Carolinas. New York: John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 0-471-16402-X.

- Davis, Burke (2002). The Cowpens-Guilford Courthouse Campaign. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0812218329.

- Fleming, Thomas J. (1988). Cowpens: Official National Park Handbook. National Park Service. ISBN 0912627336.

- Marshall, John (1832). The Life of George Washington: Commander in Chief of the American Forces, During the War Which Established the Independence of his Country, and First President of the United States. Second Edition, Revised and Corrected by the Author. Philadelphia: James Crissy.

- Roberts, Kenneth (1958). The Battle of Cowpens: The Great Morale-Builder. Garden City: Doubleday and Company.

- Swager, Christine R. (2002). Come to the Cow Pens!: The Story of the Battle of Cowpens January 17, 1781. Hub City Writers Project. ISBN 1891885316.

- Trevelyan, Sir George Otto (1914). George the Third and Charles Fox: The Concluding Part of The American Revolution. New York and elsewhere: Longmans, Green and Co.

External links[]

- Fowler, V.G. (2005). Brigadier General Daniel Morgan. U.S. Department of the Interior: National Park Service: Cowpens National Battlefield South Carolina. Retrieved on 2007-12-10.

- <templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>Hourihan, William J. (Winter 1998). "Historical Perspective: The Cowpens Staff Ride: A Study in Leadership". The Army Chaplaincy. Retrieved 2007-12-10.

- Moncure, Lieutenant Colonel John (1996). The Cowpens Staff Ride and Battlefield Tour. Command and General Staff College: Combined Arms Research Library. Retrieved on 2007-12-10.

- Parker, John W. Historical Record of the Seventeenth Regiment of Light Dragoons, Lancers: Containing an Account of the Formation of the Regiment in 1759 and of Its Subsequent Services to 1841. Replications Company. Retrieved on 2007-12-10.

- Withrow, Scott (2005). The Battle of Cowpens. U.S. Department of the Interior: National Park Service: Cowpens National Battlefield South Carolina. Retrieved on 2007-12-10.

Coordinates: 35°08′12.6″N 81°48′57.6″W / 35.136833°N 81.816°W